'Suffer little children to come unto me, for of such is the Kingdom of God'

These are the words of

Jesus, as recounted in Matthew 19:14, Mark 10:14, and Luke 18:16. Quoted by Queen Victoria.

... about The Victoria Hall ...

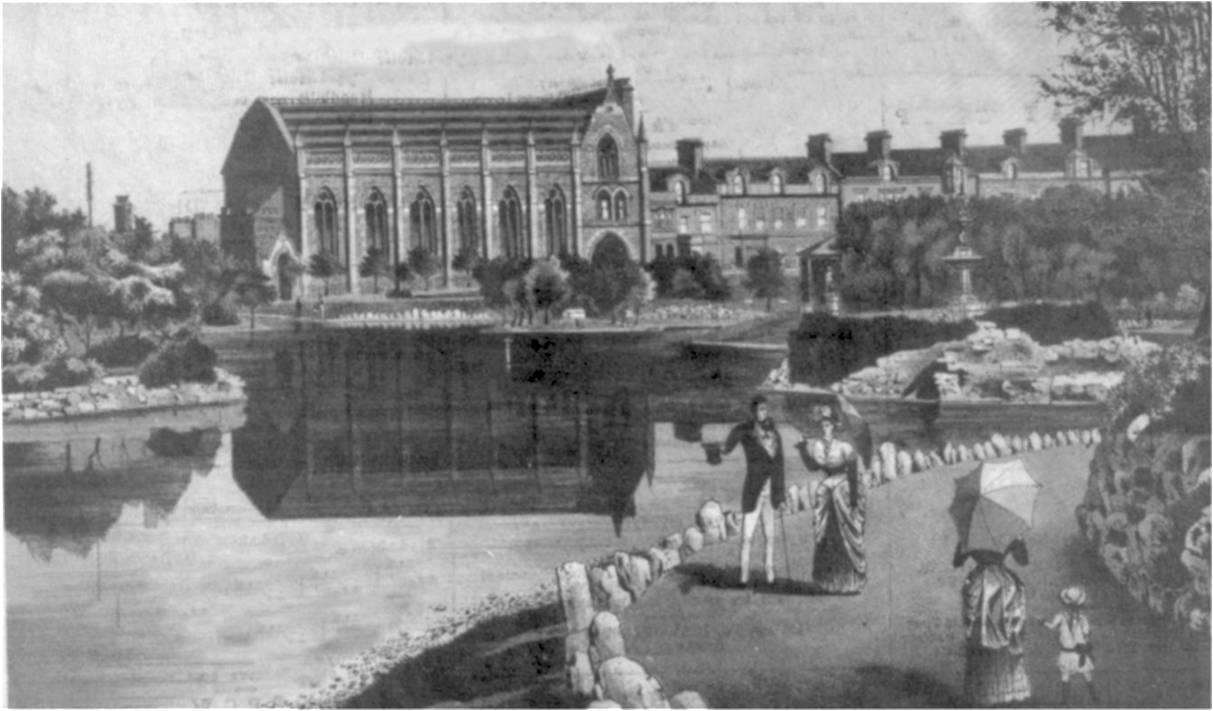

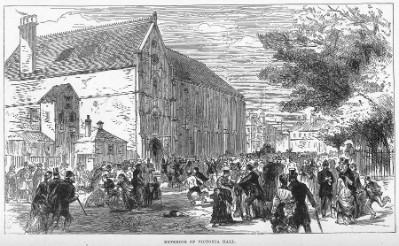

[above] Victoria Hall - Funded by Edward Backhouse [a Quaker Minister] and built in 1872.

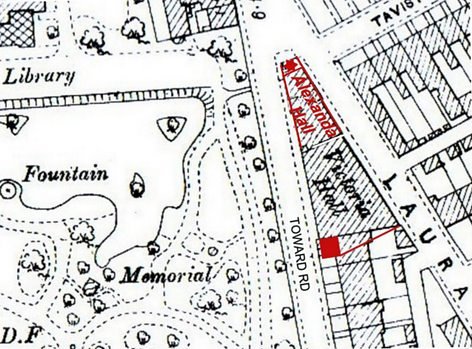

[above] The Alexandra Hall, with the original Victoria Hall in the centre. |  [above] Map showing the location of Victoria Hall |

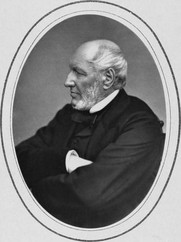

Edward Backhouse [Wikipedia]

| In the mid 1800s, Edward Backhouse was famous in Sunderland for his philanthropy.

He was a partner in the family banking firm & worked as a Quaker Minister. One of the founders of the 'Sunderland Echo', he was committed to charitable & temperance work particularly amongst the poor in the East End of the city. At the time, more affluent areas were developing round Fawcett Street. In 1870, after seeing a need for a new public hall, a site was chosen off Borough Road next to Mowbray Park, at the corner of Toward Road & Laura Street & the Backhouse family funded the building of Victoria Hall. Built in Gothic style, the hall was mainly used for social, political & religious meetings until 1883 when, as a treat for poor children, there would be a show with penny tickets. Edward Backhouse had died four years earlier but he would surely have approved his trustees' decision. The Backhouse family is remembered in Sunderland by the attractive Backhouse Park, off Ryhope Road which is on land bequeathed to the town by Edward Backhouse on his death. Early Church History to the Death of Constantine written by Edward Backhouse is available to download. |

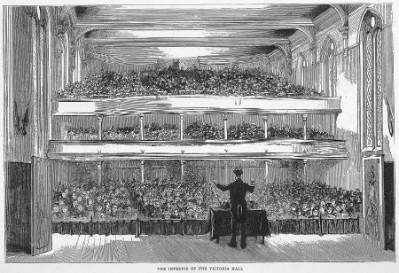

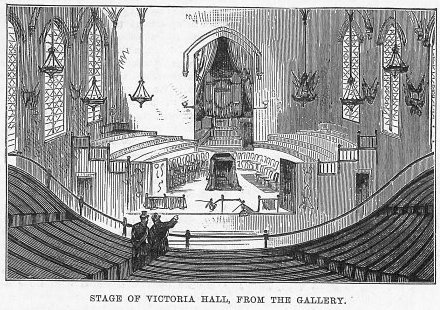

... inside the Victoria Hall ...

[above] the inside of the Victoria Hall, as seen from the stage. |  [above] The stage of the Victoria Hall, as seen from The Gallery. |

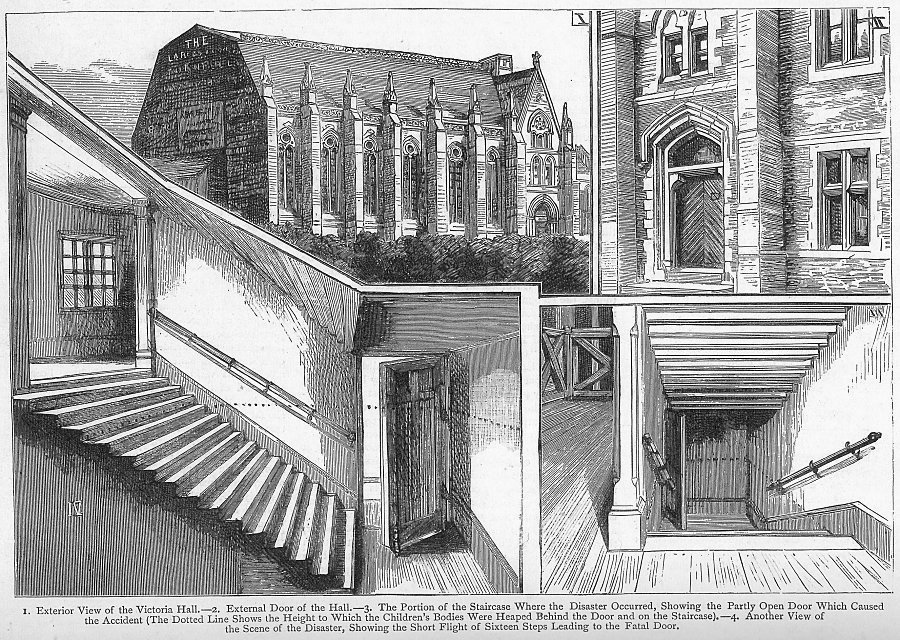

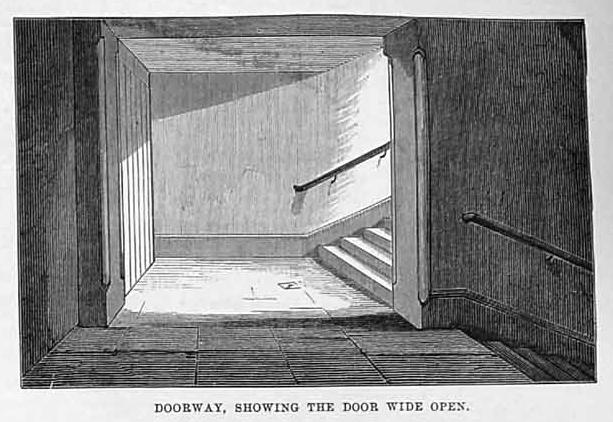

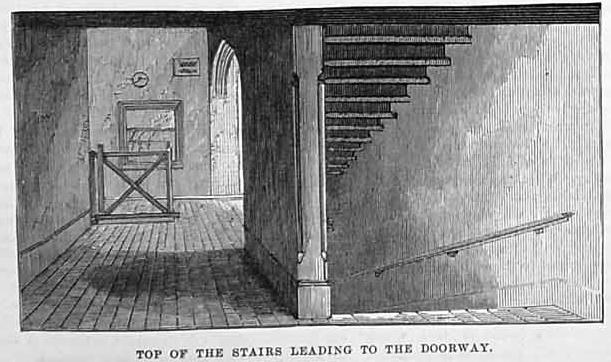

[above] 1. Exterior view of the Victoria Hall - 2. External door of the Hall - 3. The portion of staircase where the disaster occurred, showing the partly open door which caused the accident (the dotted line shows the height to which the children's bodies were heaped behind the door and on the staircase). - 4. Another view of the scene of the disaster, showing the short flight of sixteen steps leading to the fatal door.

... the Disaster ... Saturday 16th June, 1883

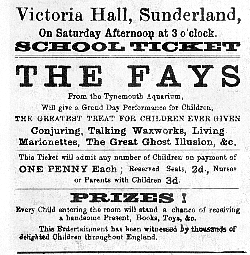

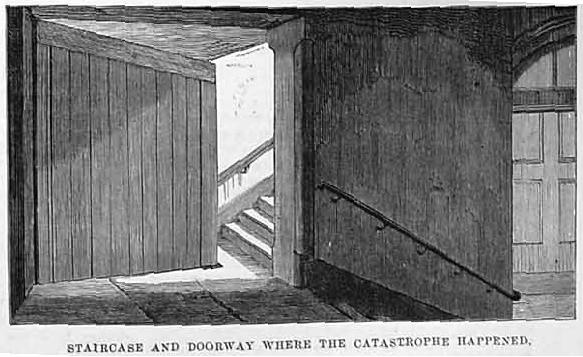

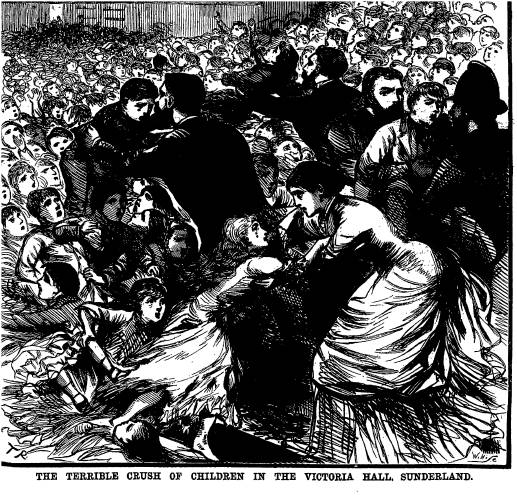

Victoria Hall, Sunderland THE FAYS From the Tynemouth Aquarium THE GREATEST TREAT FOR CHILDREN EVER GIVEN Conjuring, Talking Waxworks, Living This Ticket will admit any number of Children on payment of PRIZES! Every Child entering the room will stand a chance of receiving This Entertainment has been witnessed by thousands of | On 16 June 1883, some 2000 children aged mostly between 7 and 11, crowded in to the hall. They had been given tickets to see a show by travelling entertainers, The Fays, from Tynemouth Aquarium. Mr. A. Fay and his wife were giving a special children’s performance of "conjuring, moving and speaking wax figures and marionettes, and other diverting illusions and mock spectres," and almost all of the city’s children were in attendance with only a few accompanying parents, almost all of whom were women chaperones. It promised to be “the greatest treat for children ever given” and offered every child the chance to win a prize such as a toy or a book. As the performance ended, it was announced that prizes would be given to children with certain numbered tickets as they left. At the same time, prizes began to be handed out to those children on the ground floor. Already excited by the afternoon’s entertainment, and not wanting to miss out, many of the 1100 children in the gallery began to stream downstairs to claim their prize.  [above] Staircase and doorway where the catastrophe happened. |

|  [above] Top of the stairs, leading to the doorway. |

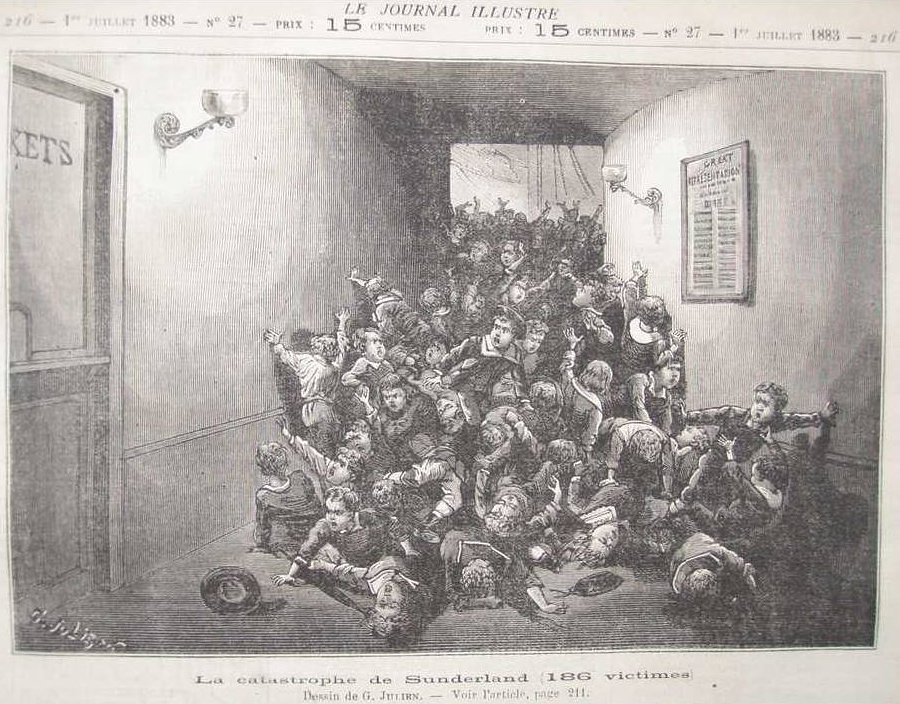

[above] image taken from the French paper, Le Journal Illustre depicting the terrible scene.

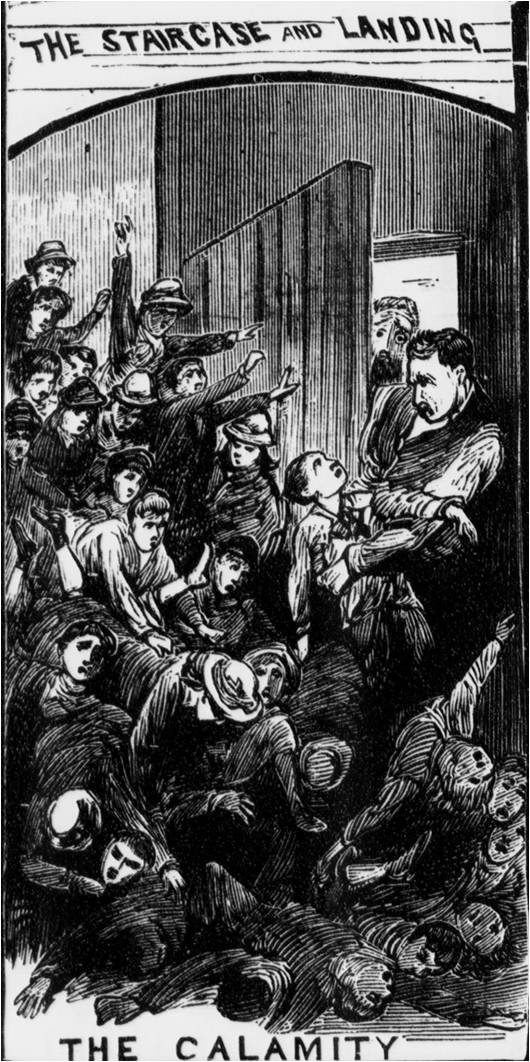

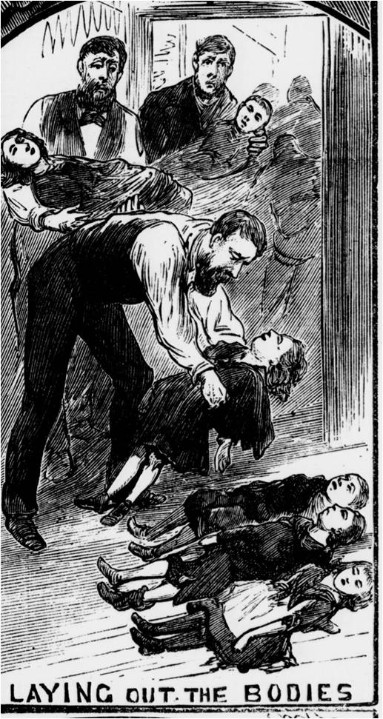

| At the foot of the stairs, the exit door had been opened inwards and bolted by the management, so as to create a gap of about 20 inches (50cm) that would allow one child at a time to leave. This was probably done to control the flow of children and make it easier to check their tickets. This situation created a death trap, for when the first child became jammed there, the next one piled up on top until the bodies were twenty deep. Those on the bottom of the gruesome heap were crushed to death as those behind continued to stampede. However, with few adults present and no one organising an orderly queue, the children simply rushed for the door. The gap was not large enough to cope with the flood of children and the narrow stairwell was immediately blocked. As more and more children surged down the stairs, they were pushed forward by those behind, who were unaware of what was happening. The children at the bottom of the stairs were crushed and suffocated by the weight of the crowd above them. The caretaker, Frederick Graham, tried to untangle the squirming, shrieking mass, but found the weight too much to lift. He then ran up another staircase and led approximately 600 children to safety by another exit. Eventually, those adults in the hall realised that children were trapped and began to pull them one by one through the narrow gap. More adults came to help and within half an hour all the children had been removed from the stairwell. A total of 183 children died in the tragedy. Some families lost all of their children. The entire Bible Class of 30 children from a local Sunday School perished in the disaster. All died of asphyxia. |

[right] another sketch depicting the scene. |  |

[above] ... concerned parents rushing to The Victoria Hall. |  |

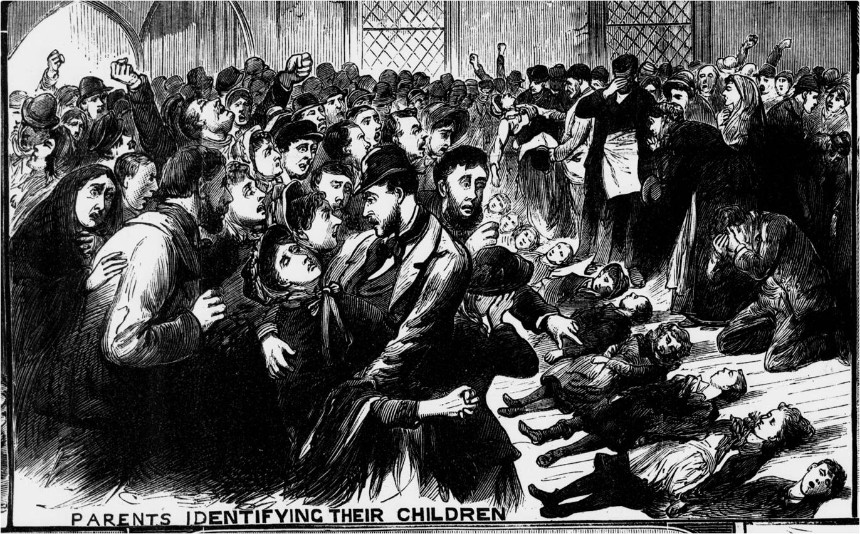

[above] an image of what must have a torturous event ... the grief-stricken parents having to identify the bodies of their children.

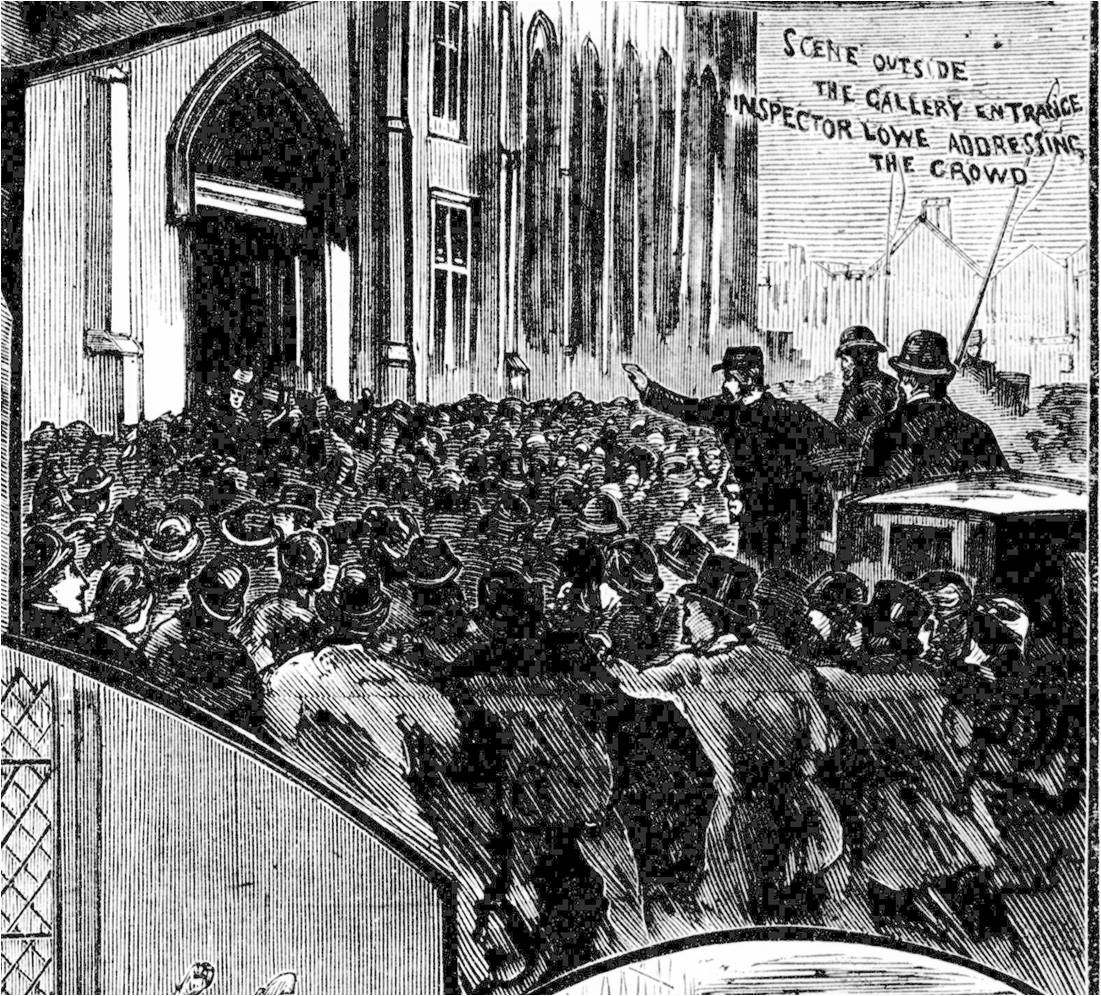

[above] scenes outside the Gallery entrance with Inspector Lowe addressing the frantic crowd.

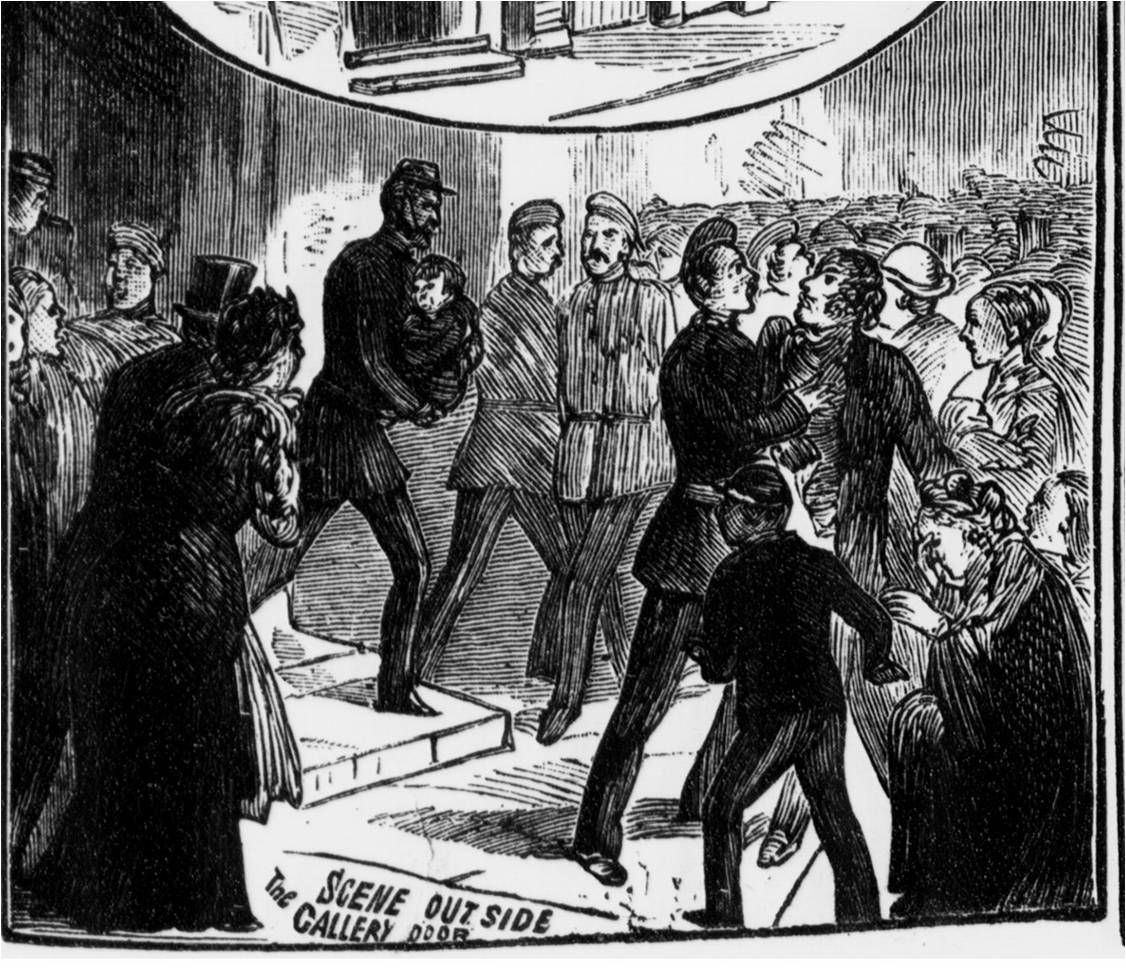

[above] scenes outside the Gallery door.

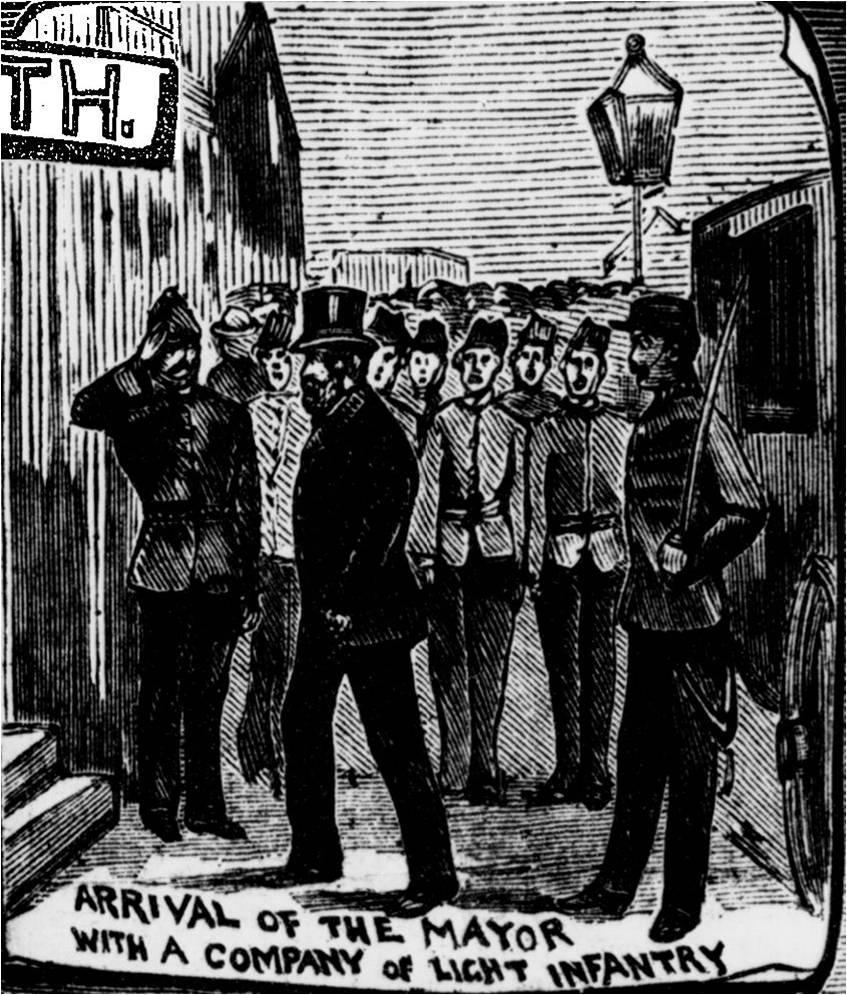

[above] arrival of the Mayor with a company of Light Infantry.

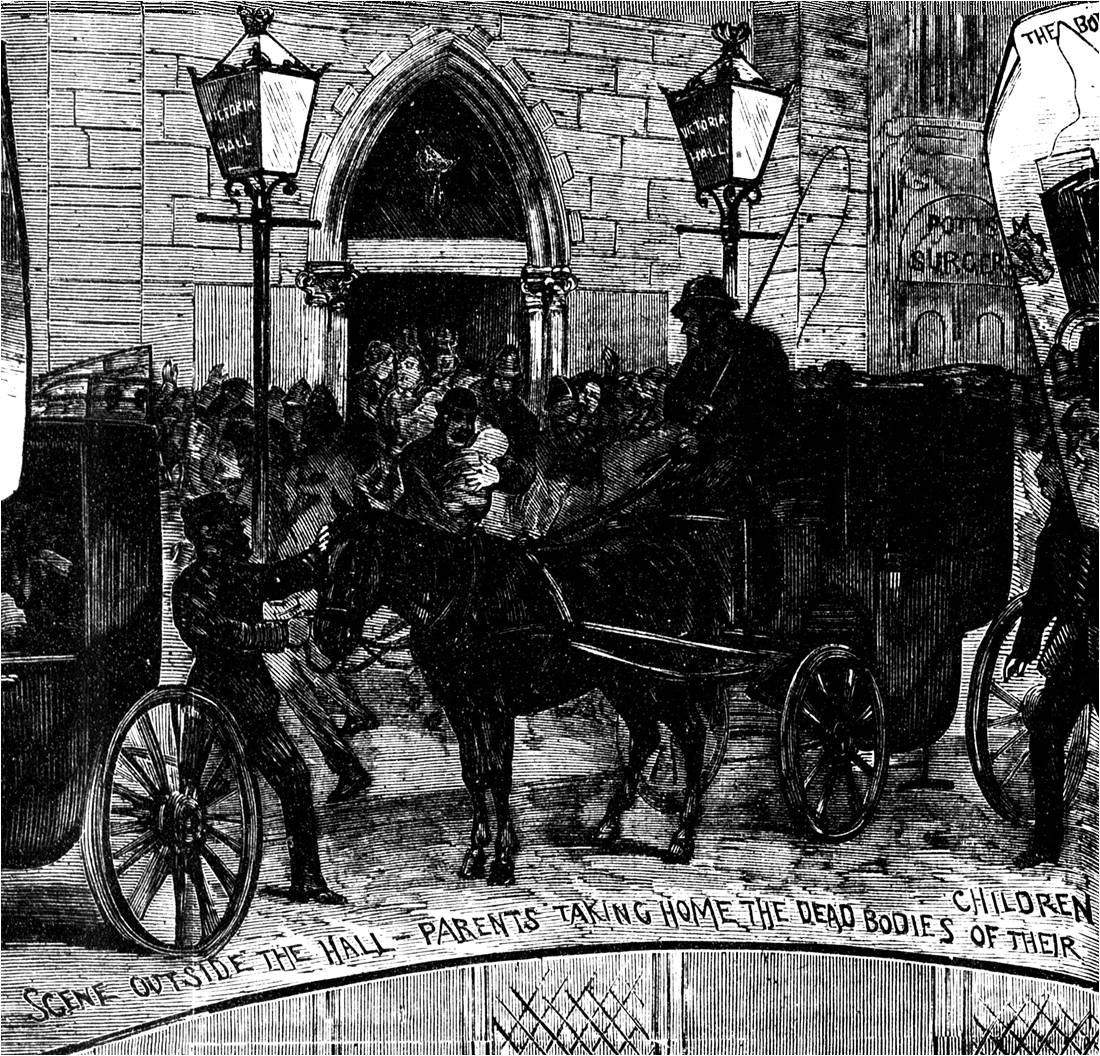

[above] scene outside the Hall - Parents taking home the dead bodies of their children.

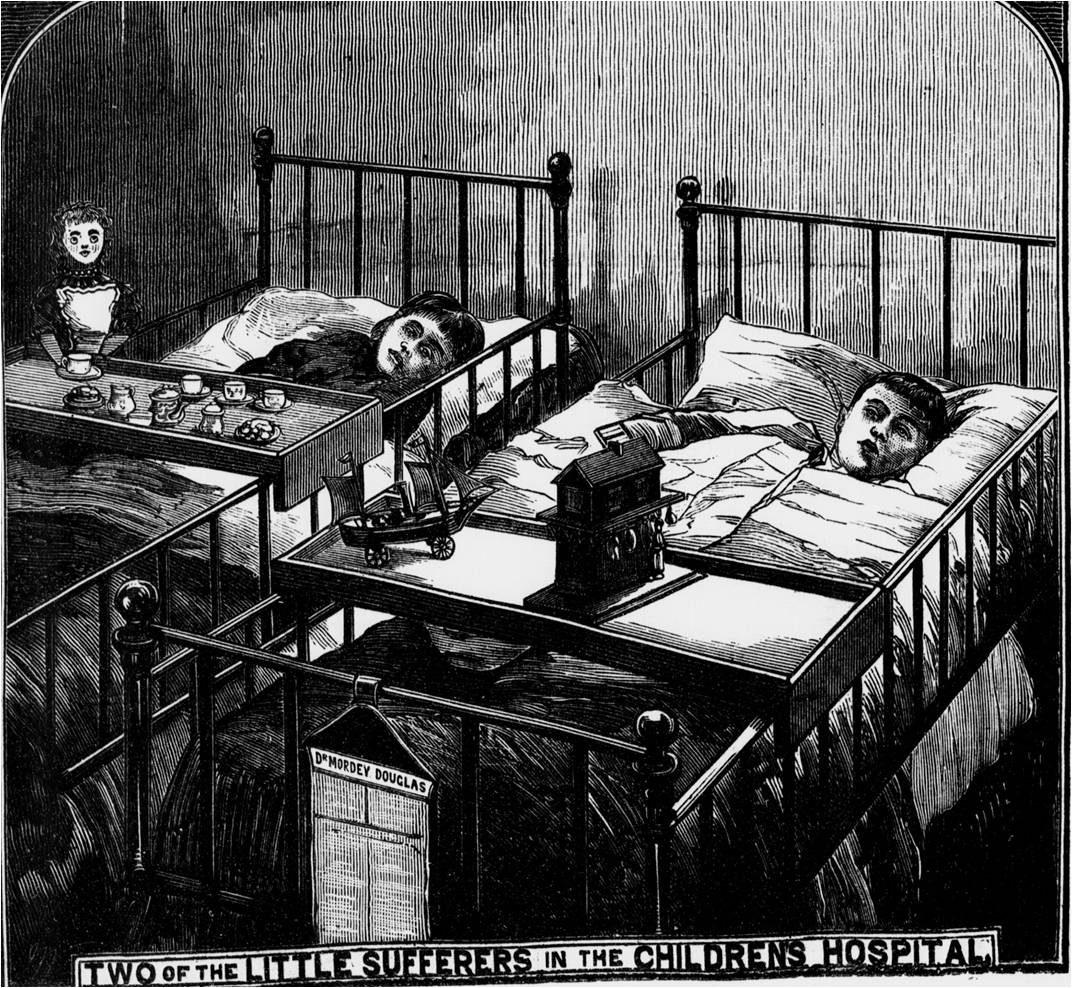

[above] Two of the little sufferers in the Children's Hospital

... after the tragedy ...

News of the disaster spread throughout the country and national newspapers ran the story.

Queen Victoria wrote to the clergymen of the town, who relayed her message of condolence at the subsequent funerals and services throughout the town. She also sent a donation towards funeral costs, and asked to be kept informed about the recovery of the survivors. Let's hope her words come true, 'Suffer little children to come unto me, for of such is the Kingdom of God'.

The Scottish poet, William McGonagall wrote a poem called “The Sunderland Calamity”, which shows the strength of public feeling at the time. The disaster fund raised over £5000, which paid for the funerals of all 183 children.

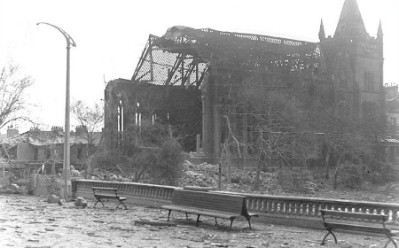

During the funerals, which lasted from the following Tuesday until Friday, all businesses in Sunderland remained closed as a mark of respect. The money that was left over was put towards the cost of a memorial statue of a grieving mother carrying a dead child. The memorial was erected in 1883 under a canopy in Mowbray Park, opposite the scene of the disaster. It was later moved to Bishopwearmouth cemetery, but restored to Mowbray Park in 2000 with a new canopy. An inquest into the tragedy was held, but it failed to blame anyone. This caused a public outcry and a second enquiry was held, but it too failed to find out who had bolted the door and who was responsible. However, as a direct result of the disaster, Parliament issued laws that required all places of public entertainment to have a sufficient number of exits, and that all exit doors must open outwards and be easy to open. Despite the horror and shock of the event, the Hall stood for another 58 years until the night of April 15th/16th 1941 when, at around 3:00 a.m. during a heavy air-raid on the town, a German parachute-mine scored a direct hit on the northern end of the building and completely demolished it. Few would have missed that sullen reminder of an earlier tragedy, but sadly several other nearby buildings were seriously damaged too, including the Winter Gardens and the Museum and Library in Mowbray Park and the Palatine Hotel at the northern end of Toward Road. Soon after WW2 the marble memorial to the dead children was moved to Bishopwearmouth Cemetery.

In 1994 Sunderland Council began a £13 million project which included a new Winter Gardens, the restoration of Mowbray Park to its Victorian glory, and the refurbishment of Sunderland Museum. As part of this project, the much vandalised marble memorial to the dead of 1883 disaster was removed from the cemetery, fully restored, and re-erected in a copper and brass protective enclosure near to its original location in Mowbray Park. |  |

Victoria Hall Tragedy Memorial

An expressive sculpture of a woman with a dead child in her lap, based on a classical statue of Niobe: she throws her head and arm back in despair. The pedestal has a stepped base and a wreath carved onto its front dado face. This sculpture of a ‘mother frantic with grief, lifting up her voice in bitter lamentation’ commemorates Sunderland’s most deeply felt disaster of the nineteenth century. A large gathering on the 18th June commenced a subscription fund for the relief of the families involved and to pay for some sort of memorial to the dead. By 14th August, £5,769 had been collected - Queen Victoria giving £50. The gleaming white memorial sculpture was ‘passed about from pillar to post’ upon its arrival in Sunderland, until eventually being set inside a glass and ironwork gazebo (approximately 6 metres high and 4 metres diameter) outside the Victoria Hall. It was removed in 1929 and an alternative site inside the City Library mooted, though it seems that local sensitivities determined its move to Bishopwearmouth cemetery in 1934. It was installed there without its protective canopy and has subsequently been vandalised and become very weathered. The inscription which used to be on the pedestal’s front dado has been copied onto a tablet which now lies at the foot of the memorial. The disaster was also commemorated by a plaque with names of the dead, glassware and a number of poems. | Inscription on Memorial ERECTED TO COMMEMORATE THE CALAMITY WHICH TOOK PLACE IN THE VICTORIA HALL SUNDERLAND ON SATURDAY 16TH JUNE 1883 BY WHICH 183 CHILDREN LOST THEIR LIVES  |

[above] The original statue, now relocated and enclosed in a canopy. |  [above] A beautiful image of the memorial. |